|

This review first appeared at the Estonian cultural weekly SIRP. You can read it in Estonian HERE

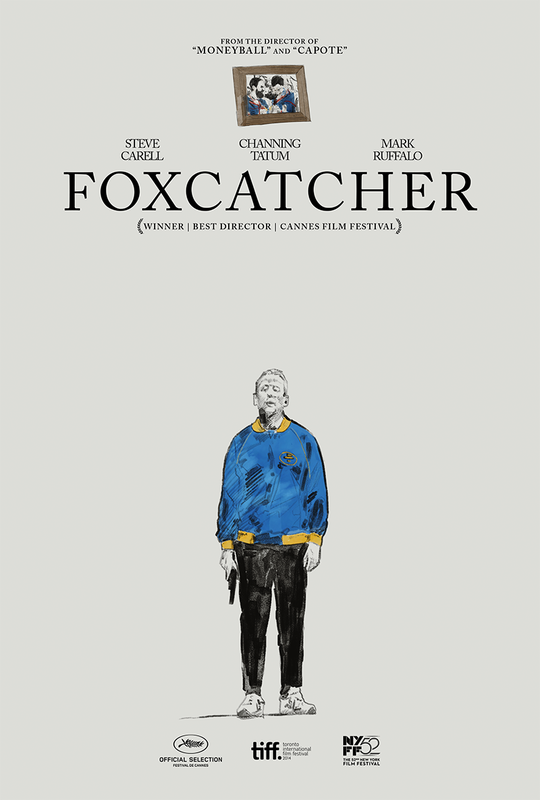

Foxcatcher (Dir. Bennett Miller, USA, 2014) The view of masculinity through the prism of modern American cinema is – very broadly – expressed in two ways. The modern Hollywood blockbuster celebrates the physical and the powerful, while so-called ‘indie films’ will often see a male negotiating a complex world in which their identity is somewhat unfulfilled and lost. Ostensibly based on a true story about amateur wrestling superstars Mark and David Schultz and their ultimately tragic relationship with millionaire John Du Pont, Foxcatcher soon reveals itself as a blend of the above approaches as it explores masculinity while dwelling on the nature of male physicality and communication. Early in the film we see former Olympic gold medallist wrestlers Dave and Mark Schultz (played by Mark Ruffalo and Channing Tatum, respectively) together for the first time, meeting up in an empty training gym. The pair barely exchanges a word, instead slapping each other and then grappling with one another. Their relationship is immediately defined by the physical and will continue to be done so throughout the film. At one point they hug each other and even this moment of brotherly intimacy resembles a collar-and-elbow tie up (the wrestling manoeuvre which begins most bouts). This is a world in which the verbal and the emotional are subordinated to communication through the body. Despite the fact that there is only one year age difference between the two, it soon becomes clear that Mark is the more child-like of the two brothers. Dave has a wife and children and seems more comfortable in a domestic setting while Mark is quiet and constantly on edge (indeed, early scenes of him sitting alone in his house eating cereal evoke images of a surly teenager). When John Du Pont (Steve Carrell) comes on the scene to offer to let Mark come to his ‘Foxcatcher’ mansion in order to train for the 1988 Seoul Olympics, it is apparent that Mark is not only embracing the opportunity to take advantage of the facilities offered by the multi-millionaire but also to escape from out of his brother’s perceived shadow. The relationship between Du Pont and Mark at first seems a paternal one. Du Pont is certainly the most verbose of the male characters we have encountered so far and he gently encourages Mark with stirring speeches. But these rousing orations have the ring of cliché – he talks of making America great and serving the country – and his words hide yet another man unable to express his feelings. Bowed by his domineering mother (Vanessa Redgrave, who – aside from Dave Schutlz’s wife - is the only significant female presence in the film), Du Pont craves both attention and adulation. Subtly manipulating Mark (including introducing him to cocaine), Du Pont is intent on having an Olympian that he can claim credit for whilst changing his mother’s mind about what she considers a ‘low’ sport. There’s a slight element of homoeroticism in the relationship between Mark Schultz and Du Pont. One wrestling session between the two is shot almost as if it’s a sex scene while at one Mark cuts and dyes his hair, as if making himself beautiful for a new lover. This element once again deals with the unsaid and the inability to express feelings in anything other than a physical way. This element has led to criticism from the real life Shultz and it does make one think about how the film takes liberties with the reality on which it is based. Whilst it seems sometimes churlish to blame any film for changing a true story in order to make its narrative more cohesive and streamlined, any work that makes a virtue of being based on said true story (especially one in recent memory) must face criticism when these omissions would seem disruptive. Aside from certain issues with the timeline of events, the film’s biggest omission is the subsequent diagnoses of Du Pont suffering from Paranoid Schizophrenia. While it would have made the film more complex, it seems too big of an issue to brush aside completely. The cinematography from Greig Fraser (responsible for the likes of Zero Dark Thirty) emphasises just how lonely and isolated the lead characters are when they're removed from anything requiring physicality. There is constant use of shallow focus within the large and empty locations (such as Du Pont’s Foxcatcher Mansion) in which the characters seemed dwarfed by everything around them, coupled with dour and washed out colour schemes. This marked out loneliness is juxtaposed with the closeness and intimacy of the wrestling scenes that teem with life and passion. It’s also worth mentioning that this is a remarkably chaste movie, containing only a modicum of swearing. In a male dominated sport, one would expect the expletives to be flowing like water but it seems that even this kind of emotional verbalisation is verboten within the world of the movie. Once again, everything has to lead back to the physical. Much has been made of the lead performances with Steve Carrell (swathed in prosthetics) getting the majority of attention. While there is a certain amount of hyperbole within this (as there often is when people want to talk about a 'comic actor turned serious'), it is an engaging performance that shows restraint with Du Pont’s obvious emotional problems bubbling under the surface. Tatum is something of a revelation managing to turn stillness and economy into something of an art. With a powerful physical presence he manages to convey much while saying relatively little. But it is Ruffalo who is perhaps the stand-out here. With little physical touches (walking with a stiff and awkward gait showing his years in the sport) alongside a sympathetic performance, Ruffalo places Dave Schultz at the emotional heart of the movie. Out of everyone he is the one at most peace with who he is, a fact that renders the inevitable conclusion of the film even more tragic. Indeed, the sparse lead performances emphasise one of the most remarkable thing about Foxcatcher. Despite its ‘Indie’ credentials, the film is a product of a major American studio . And it’s a film that revels in stillness and solitude: as if Bela Tarr had accidentally been let on-set of a Hollywood blockbuster. It's this unique aesthetic combined with a take on gender usually unexplored by American cinema, that makes Foxcatcher such a rewarding experience. While there are other readings to take from the film (Du Pont’s character is as much an indictment of the moral decadence of the American elite as it is of his individual upbringing), Foxcatcher plays with something that is almost a ‘Catch 22 of masculinity’: How men must keep their emotions in check despite the fact that there is danger inherent when these emotions aren’t expressed. |

AuthorJournalist. Filmy type person. Likes crisps. Archives

December 2015

Categories |

| Laurence Boyce |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed